For one Utah-based photographer, Johnny Adolphson, the path to capturing the wilderness was a natural evolution rooted in a lifelong relationship with the outdoors. Years spent working as a ski patroller, wildland firefighter, and mountain guide built the foundation not just for technical resilience, but also for an intuitive understanding of wild spaces. In 2011, Johnny’s casual hobby began to take shape as something more meaningful. By blending his rugged outdoor experience with a growing passion for photography, he carved out a distinct place for himself in the landscape art world.

What started online—selling images through social media—has grown into a thriving business that now includes art shows, vendor markets, and partnerships with local businesses and breweries. It’s become a full-time career, not just for Johnny but for his wife Sherry Adolphson as well, who manages the business side of the operation. Together, the couple has built something deeply collaborative, grounded in years of working side by side across various industries.

You may recognize Johnny’s work from past issues of this very magazine. His images—often showcasing Utah’s dramatic landscapes and seasonal beauty—have graced several covers over the years. Now, for the first time, the photographer behind those images takes center stage.

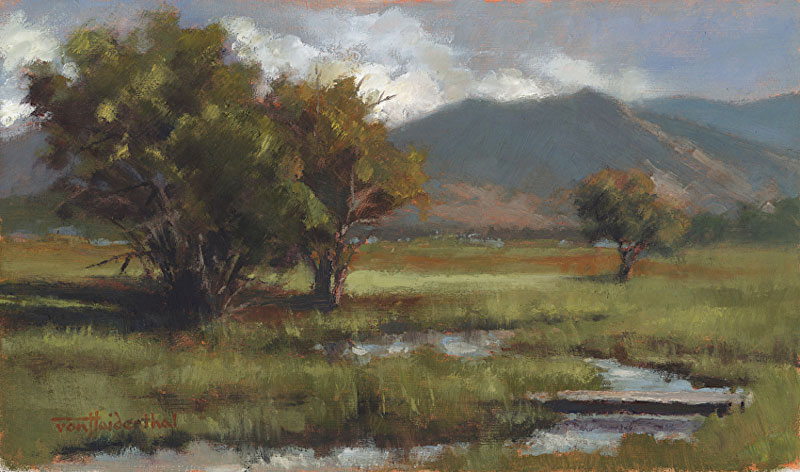

Johnny’s camera lens is often turned toward Utah’s rugged beauty—an area he considers his specialty—but his travels have taken him from the Tetons to the Canadian wilderness. Local mountains like Timpanogos, blooming wildflower meadows, and stretches of open farmland remain some of his favorite subjects. Though he has trekked deep into remote wilderness and faced off with wildlife, some of the most challenging moments of his early photography career came not from nature, but from the chaos of shooting weddings. In contrast, nature’s unpredictability feels more fluid—storms may interrupt a plan, but often lead to unexpected beauty.

Much of his process is guided by instinct. A planned shot may be completely abandoned in favor of something else that emerges in the moment—like a sudden burst of flowers, dramatic lighting, or an unexpected weather shift. Over the years, participating in art shows has given him insight into what resonates with viewers, yet his artistic choices are still driven by personal vision rather than trends. He acknowledges that while some of his more iconic Utah images perform well commercially, it’s often the less conventional ones that hold deeper meaning to him—images shaped by patience, light, and intuition.

Johnny recalls a few of these moments, “Mesa Arch— the most popular arch in Utah— I pulled up and stood there with the masses and got my shot. Last summer, I was down in Moab for the Art Festival, and I drove out there again. The parking lot was full, but I’ve always gone to this spot called Buck Canyon, just down the road. I like to cook breakfast in my van and chill there after shooting the sunrise. I was the only person there, and I got this amazing image of a lone dead tree. The tree formed this symmetrical light pattern between itself and the canyon in front of me, with clouds rolling over the La Sal Mountains in the background. That shot’s actually been a nice perform— but to me it’s meant way more than the Mesa Arch shot.”

The emotional response Johnny’s work evokes in others is what keeps him going. Whether his images hang in quiet homes or bustling office spaces, his goal is to bring serenity and wonder into people’s everyday environments. For him, landscape photography isn’t just visual—it’s a kind of emotional preservation.

That sense of responsibility extends beyond the frame. He’s contributed to environmental efforts by donating work to conservation groups and land trusts.

Some of the fields and barns he’s captured no longer exist, lost to rapid development in the valley. He reminisces, “Recently, Sherry dropped me off at Guardsman’s Pass, and I hiked up to a photo spot from there, but just five years ago, I was driving up and parking right at the top. A lot of the fields and barns that I’ve photographed in the valley here… those scenes aren’t there anymore due to growth and houses.” Johnny’s photography, in a way, becomes both art and archive—evidence of what once was.

There have been unforgettable encounters along the way—from standoffs with a mountain lion to surreal human moments deep in the backcountry. “There’s a place called Gooseberry Mesa,” Johnny shares, “Where one day I came across an encampment with some young adult males that were outcasts from a polygamous society who had set up their encampment where I do shoots. They were armed and had all sorts of signs quoting scriptures and warning people to stay away, even though they were on forest service lands. I just let them know that I was shooting there and went on my way.”

These experiences are part of what has shaped Johnny’s grounded approach. Through it all, the advice he offers to others looking to pursue landscape photography is simple but essential: watch the light, and build everything else around it.

With new projects on the horizon—including the opening of a gallery right here in Heber at the old fire station in mid-August—there’s a sense that the journey is still unfolding. Future travels may take him back to beloved regions like Washington’s Palouse or the Sierra, but it’s clear that Utah will always be at the heart of his work.

Behind the scenes, Sherry plays a vital role in sustaining the momentum. Her background in landscaping and business management made her a natural fit for running operations—from inventory and customer tracking to financial planning. Together, they’ve built a lifestyle rooted in independence, passion, and shared purpose. It’s a life that requires grit and flexibility, but also offers deep rewards—like hearing from customers who cherish their artwork or watching their images find a place in someone else’s story.

Sherry expresses her gratitude, “It’s incredibly rewarding. Everywhere we go now, we hear things like, ‘Hey Johnny, we have your art in our home.’ Or, ‘We gave one of your prints to our son for his birthday—he loved it.’ When young people, like college or high school students, come to our Art shows and spend their hard-earned money on a little paper print—and they’re excited about it—that’s really cool and very rewarding.”

Even now, after years of honing his craft, Johnny considers himself a lifelong student of photography. The learning never ends, and neither does the desire to create. For him, this is more than a career—it’s a calling that continues to grow, frame by frame.

You can see Johnny’s work on Instagram or Facebook and at johnnyadolphsonphotography.com